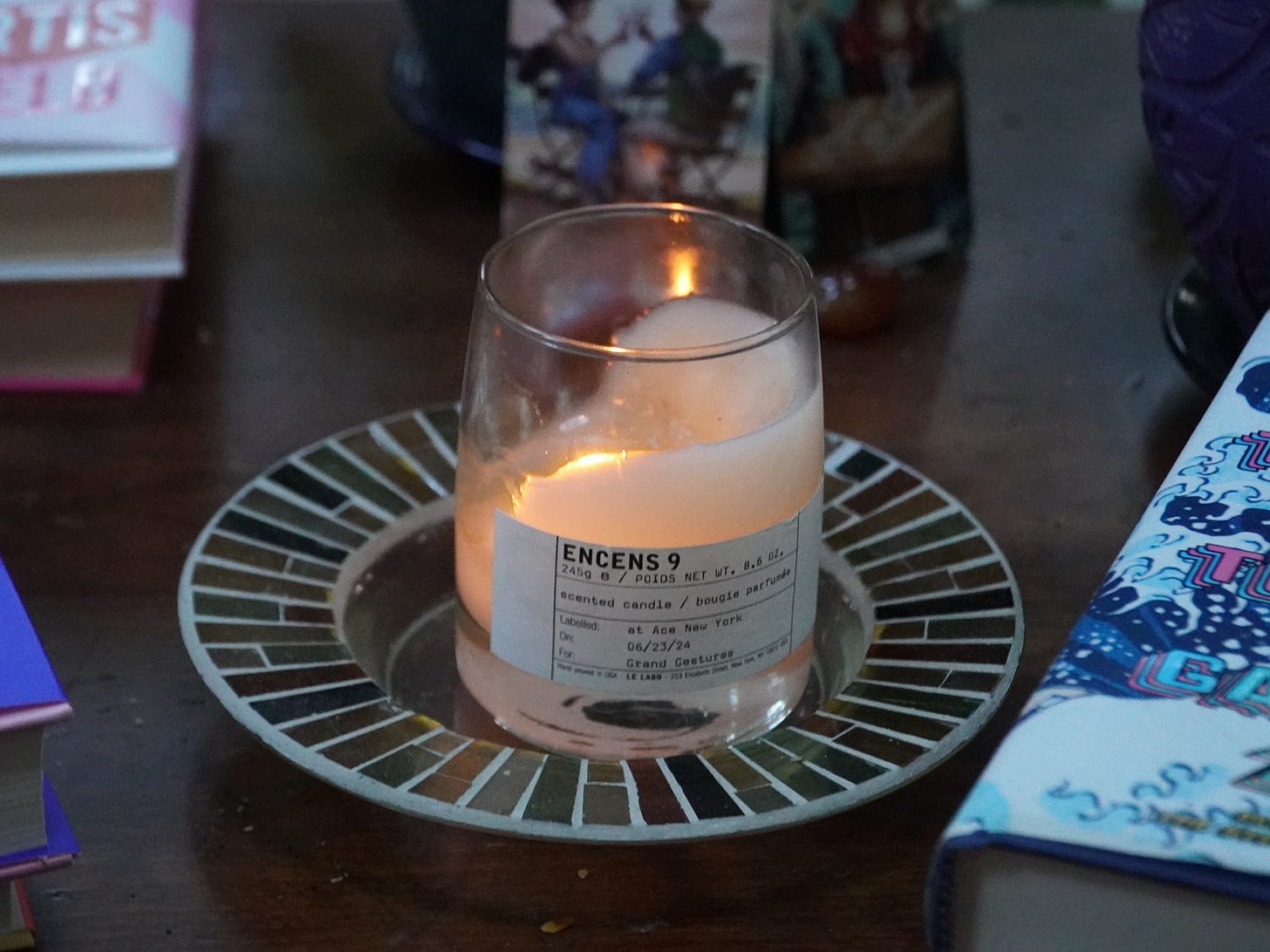

If you read my last post, you may remember that in June I went to the exhilarating (and nerve-racking) Write to Pitch Conference in New York and pitched my novel to agents and editors. While there, I came to the sinking realization that my manuscript was too long. Even so, it wasn’t all doom and gloom. Some of the people I pitched to had, after all, requested I send them Grand Gestures. But at 124,648 words, the novel was a hard sell for a debut author. I came back to Pittsburgh armed with the certainty I needed to cut the novel and a too-expensive (but hey, broken heart) incense-scented Le Labo candle I bought while hanging out with my fellow conference attendee and new friend Jess Ridlen. I kept turning the conundrum around in my head: how do you cut a novel you’ve painstakingly revised over five drafts so that each scene leads to the next and every character adds their own variation on the novel’s themes? My novel was a Jenga tower, and I worried that any piece I removed would cause the structure I’d built over three years to collapse into a messy heap no agent or editor could possibly want.

Luckily, I didn’t have to figure it out on my own. Turning to people who know what they’re doing saves a lot of grief, and it so happened that I had someone in my corner who knew exactly what he was doing. I’d been working with author and screenwriter Mark Jude Poirier on the query materials I sent to agents. I’d chosen Mark because he’d published award-winning novels and short story collections, and he’d written the screenplay for Smart People, a sharp and moving dramedy about a cranky academic who gets a second chance, starring Dennis Quaid, Elliot Page, and Sarah Jessica Parker. Like me, Mark straddled the fiction and film worlds, and his feedback helped me improve my writing without compromising my voice and vision. I asked Mark to look over the first 65 pages of Grand Gestures and asked him to flag any Jenga pieces that could go. As always, Mark’s advice was brilliant:

Stay true to (but also play with) your genre

Mark knew that you start with what works. Not only because it bolsters the writer (which it does), but also because it’s useful to know what you’re doing well. You don’t want to remove the pieces that hold your tower together, after all. Mark said I was “really good at handling a lot of characters” and that “it reads like an upmarket women’s fiction book” (big relief since that’s its genre!) but “feels more organic.” He went on to say, “You honor the genre well, but you go in unexpected directions that are fun.” He also had some thoughts on the novel’s movement. “I admire that it’s moving. So much of what I write and read could benefit from moving, and yours moves. These moments of humanity are really moving your manuscript.”

Watch the speeches

The novel might be moving, but it was still too long, and Mark had found a way to cut it. While my short dialogue exchanges were fun and sounded natural, he said that “when you have something coming out of someone’s mouth that’s longer than two lines of dialogue, it’s going to sound like a speech.” These weren’t “I Have a Dream” kind of speeches. No one was going to clap at the end because “the longer stuff feels expositional, wooden, heavy handed.” When I started looking over the pages he’d read, I realized that he couldn’t have been more right. My witty, congenial characters would turn into automatons as they took over the page, talking at their poor interlocutors. People think writing is a solitary endeavor, and it does require you to be on your own for hours, but you desperately need people to lift the curtain on your story’s foibles and mishaps—and when they do, you see the world you’ve created anew.

Don’t have characters tell each other what they already know

Mark also said, “I got this fellowship from Paramount to learn how to write screenplays. I had this amazing mentor who said if a sentence begins with the clause, ‘As I keep telling you,’ chances are what follows will be heavy-handed.” In other words, the only reason that particular dialogue is uttered is that the reader needs that bit of exposition. But readers are smart. They can tell when the characters aren’t doing something for themselves but for the reader, and it takes them out of the story. It turned out that I could live without most of the stuff that was in the speeches, but it was a lot harder to come up with natural ways to deliver my exposition. I’m glad I did, though, and that my characters weren’t forced to say things to each other they naturally wouldn’t.

What’s with the chairs?

I’m not a writer who thrives on description, which is why I could never write fantasy and build a new world for readers. But it seems I have a thing for chairs. Mark said he “felt grounded in the description, but there were a lot of chairs,” and most of them were green. “If there are different chairs, if one of them is a lounger, describe them as a lounger.” It turns out even description minimalists like me can overdo it, but I was glad he gave me the diagnosis and the solution. Yes, we now have a few loungers, and they’re not green.

Don’t overdo your conclusions

Mark pointed out that I had a penchant for ending my sections with concluding sentences that would be more meaningful at the end of chapters. This was delightful to learn because, unlike the dialogue and the chairs, which needed rewriting, these could just be cut. Poof! Press a key and those extra words are gone, and the writing was tighter and better for it.

Fulfill those wishes

You want to leave your writer energized and ready to tackle the changes, so Mark left me with these words, “This whole genre is about wish fulfillment. But the more you connect it to reality, the more the wish fulfillment feels real, and that’s what you’re good at.” I was happy to learn that I was skirting some line between what we want our lives to be like and what they’re actually like, and that happiness kept me going as I cut, and cut, and then cut some more.

For weeks I sat in my plant and book-filled office with the Grand Gestures candle lighting my way and Mark’s words reverberating through me. My brain went into a freaky word-cutting mode as I questioned every sentence. Do we need you? And if so, do you need to be this long? I feared I’d weaken the playful lyricism I’d worked so hard to craft, but as I reread my revised chapters, I felt like it was still there, but more streamlined. I asked my husband Nate, who has patiently and lovingly read every version of this novel, to read it and tell me if he thought something was missing. He returned Part 1 to me with a glowing smile, and we marveled at this rewriting miracle. I had kept my characters and most of my scenes, but the word count was shrinking.

On July 15, I got a request for the full manuscript based on the first chapters I’d sent when I queried this agent. This wasn’t just any agent, but someone who represents one of my very favorite authors (a writer whose books many of you have probably read). Problem was, I didn’t have a manuscript to send them. Mark advised me to be honest about my cutting frenzy and request an extension. The agency was incredibly gracious, but I felt even more pressured to get the words down. Trouble was, our yearly trip to New York was coming up. So off we went.

We stayed with my beloved David and Kathy Tyson, and the boys got to hang out with their parrot:

We did shamelessly touristy things, like going up the Empire State Building:

We paid the Egyptian wing of the Brooklyn Museum a visit:

I stopped seeing the world as words to be slashed and enjoyed our time in the city, but the word count kept ticking like a bomb in the back of my mind. When we got back, I returned to my office and kept questioning my sentences until on August 8, when I sent the agent my 106,285-word novel. I’d cut 18,363 words (14.7%), and the Jenga tower still stood. It’s still a little long, but not prohibitively so. And no, I haven’t heard back from said agent or the others who requested the manuscript. Publishing is slow, so I’m working on honing my patience skills, which are not nearly as sharp as my word-cutting ones.

Unearthed Photo

In June of 2010, I took another exhilarating and nerve-racking trip to New York to spend a month interviewing and filming the lives of four immigrant women for what would become my 2014 feature documentary Vanishing Borders. I got home with endless hours of footage and spent years cutting it to a 90-minute film. At the time, I wanted to expand narratives around immigration to include stories of women immigrants who’d come to the US and were making their communities better through their professions, their interactions with others, and the compassionate wisdom with which they faced their lives and those around them. As much as the film felt necessary back then, it feels downright vital ten years after I completed it. I don’t want to give Trump any more of the attention he’s so gifted at getting, so I’ll just say that Vanishing Borders counters his monstrous portrayals of immigrants with stories of love and perseverance. It celebrates the ways people from different cultures can uplift each other when they come together.

I have added it to my YouTube channel in whole:

You can also watch the stories of Yatna, Daphnie, Melainie, and Teboho individually. As always, please consider subscribing and sharing. The engagement convinces the algorithm gods that the work matters and should be recommended to other viewers—and in this case, I think these four women’s stories do matter, and they’ll help us counter so many awful narratives swirling around us this election year.

Stories that Transfixed Me (and May Transfix You)

My friend Andrew Wille spent months reminding me I had to read Tom Lake because I’d love every second of it, and I kept telling him I needed to wait until I could give it my full attention. That time came after I completed my streamlined manuscript, and Andrew couldn’t have been more right. Ann Patchett’s latest novel follows Lara Kenison as she spends the pandemic alongside her husband Joe and their three college-aged daughters picking cherries in their Michigan orchard. To pass the time, the girls ask Lara to unspool the crackling tale of her past as an actress who dated a legendary movie star. Told between two timelines, the book is a meditation on memory and secrets and how certain paths can remain separate yet strangely intertwined in ways that enrich (and complicate) our lives and those of everyone we love.

Hacks, created by Lucia Aniello, Paul W. Downs, and Jen Statsky

If you haven’t fallen in love with Hacks yet, this is the perfect time to start. Season Three just garnered Emmys for Outstanding Comedy (and you will laugh!), Writing in a Comedy Series (the dialogue makes me audibly gasp with joy), and Outstanding Lead Actress for the ever-brilliant Jean Smart, whose aging stand-up comic legend Deborah Vance is one of the titular hacks. The other is Ava Daniels (Hannah Einbinder), an up-and-coming comedy writer who tries to revitalize Deborah’s career while helping her find her humanity and face her mortality. In the meantime, Ava does plenty of finding and facing of her own. It’s biting, a little sweet, and always delicious. I hope the Emmys keep coming so we get to continue to watch these women evolve.